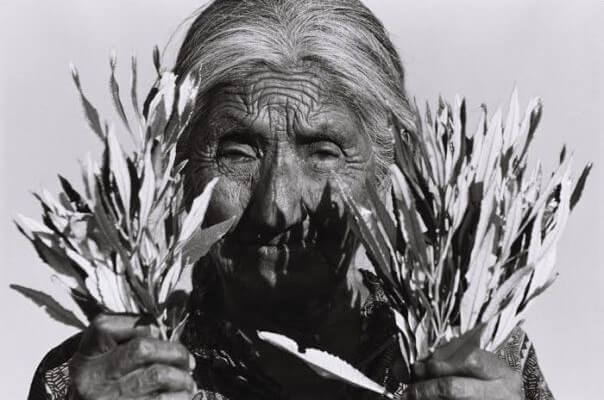

The Role of Cochimi Women

Leaders or Followers?

When the Jesuits came to Baja they brought the European notions of specific men and women’s roles with them. They tried to implement these roles into the guidelines that formed the basis of mission life. This manifested itself in the following:

Women worked and slept separated from men.

Women were supervised in all aspects of their lives.

Women were given agricultural duties.

Housekeeping duties also fell to women.

Child rearing duties were women’s prerogative.

The Jesuits were intent to make changes and as such there is little evidence of what traditional women’s roles were in Cochimi culture. However, all the mission reports indicated that the women worked as hard, or harder at food gathering and processing chores, than the men did. The heavy work of grinding seeds using Manos and Metates would have been quite grueling, requiring a fair amount of strength, dexterity and stamina. The women then, were not weaklings It was also noted that once tasks had been assigned to the women they were quite capable of maintaining a reasonable level of productivity without constant supervision. This suggests, and is borne out by studies in other emerging cultures, that the women performed these food gathering and processing roles in their historical culture. I have found that in some geographic areas in Baja where seeds were harvested and ground, that there can be found numerous metates within a few meters of each other.(Piedras Pintados for example) This implies that the grinding of seeds was a shared process done by many women and that it undoubtedly encouraged social interaction between the women. I also believe that these seed grinding occasions would have been relatively happy times for the women and would no doubt give occasion to complaining about their menfolk’s lack of work ethics. . . as can still be observed in similar situations today. Hmm!

It was observed that the Cochimi women and men seemed to exhibit little or no responsibility for the children of the clan. Within the rancherias the children ran loose without adult supervision once they had the capability to feed themselves.

Women also seemed to have more than one sexual partner and exhibited no attraction to only one man. This seemed to be normal in all the Cochimi rancherias and would enhance the notion of the solidarity of the group versus individuality thus providing a more stable social environment especially during times of food shortages.

Also observed was the fact the women in general, rather than a few individuals, performed midwifery duties and that these skills were more than perfunctory. Babies still died at birth however, no doubt due to complications beyond the level of expertise of the midwives. Abortions and infanticide was observed in the rancherias, but strictly forbidden in the mission environment.

Women were observed to have a degree of expertise in searching for, and processing, the various herbs and potions used in the remedies practiced by the Cochimi. Sometimes that was done by men also, so it would appear that deference was given to those who were competent rather than a hierarchal selection based on sex or social standing. This again points to an successful egalitarian society.

Women would not have been expected to provide food by hunting. Although in some cultures, setting of snares for small animals and gathering of grubs and insects is done by women and more adept children. I expect the same in the Cochimi culture. Remembering that the social rules and traditions were working well before the arrival of the Jesuits, it can be assured that the Cochimi women supplied an important and often crucial role in the everyday life and survival of their clans.

Women also played important roles in the dances performed during fiestas. These dances have been described in the padres reports but the reports focused on the entertainment value of the dance rather than the teaching and story-telling role it, no doubt, provided to the clan members. Documented however, were descriptions of dances, designed to give instruction as to how to fish, hunt, make war, pack a load, travel, carry babies. In all, more than thirty different dances were observed. It was noted that all participants took their roles in the dance seriously, even any of the young infants who participated. Dances of this nature are found in other cultures in the Americas, most assuredly in environments where there is no written language used to pass on tradition and cultural history. Dance in this sense then is an important tool that asserts a social cohesion.